I’ll never forget the day I received my first shipment of books. I eagerly leafed through the pages with a feeling of elation. Finally! The years of pouring my heart and soul into writing, revising, editing, proofing, and the many invaluable lessons learned along the way—not to mention the million pots of coffee—had culminated into my first published book. A dream come true!

If I could do it all over again—perhaps a sequel in the near future—boy, would I ever change a lot of things! It is for that reason that I want to share my journey—which at times was rougher than a washboard road—from writer to published author with you. For all you writers out there who are working on a manuscript or just finished one and are now ready to publish, this is for you!

When I neared the completion of my manuscript, I became giddy with anticipation that I would soon be an author. I truly believed that once I typed “The End” on the last page of my manuscript, all my hard work would be over, and I would send it out to a few publishers, and one of them would gladly snatch it up in a heartbeat. After all, I believed I had a great story and, besides, I wrote it to the best of my ability, and I checked and double-checked my spelling and grammar. What else was there? Well, let me tell you. Rejections! That’s what. One after the other. What a letdown. Where was a “Rejected Anonymous Group” when I needed one? However, I picked myself up, squared my shoulders and moved forward. I was too invested in this project to give up now. It was time to search for a professional editor.

Editing

After learning that most editors will give a free sample of their work, I sent a copy of the first few chapters to editors as far away as California and New York and everywhere in-between. As the samples poured in, my eyes hungrily devoured the pages. Ironically, the best editing job—hands down—came from right here in my own state of West Virginia; Inspiration for Writers, Inc. But, as ill-fate would have it, the promise of a “good” comprehensive edit for a much cheaper price by a different company won me over. I convinced myself that it would be a “good enough” edit and I could save myself a lot of money. Right? I couldn’t be any more wrong! When the edit came back it wasn’t anything more than a proof. Many of the pages didn’t even have a red mark on them. I knew that my book could be so much more, and in the end, we really do get what we pay for. If I wanted my book to be the very best it could be—and I did—I knew what I had to do. I turned back to Inspiration for Writers, Inc. It was the best decision I could have made for my book.

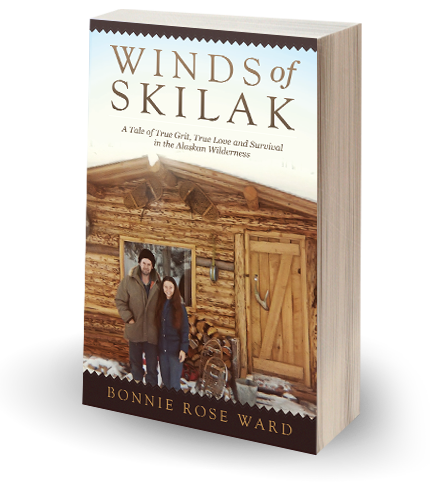

Over the course of a year, Sandy Tritt, Rhonda Browning White, and I diligently worked on my book. Not only do those ladies go above and beyond—trust me, they do–but through it all, they made it fun and easy, they taught me so much, and they did it all without changing my story or my unique writing style. Besides hiring a good editor—and I advise that you do so because it’s hard to see all of your own mistakes or to look at your work objectively—I also can’t stress enough the importance that you, the author, must take full responsibility to see that your manuscript is in top-notch shape and the best it can be before you consider publishing. That means working with your editor, revising, proofing, proofing, and proofing some more. Some of you may be thinking, “But I want to publish my book now.” So did I, but I’m glad I didn’t rush into it. Be patient and do what you’ve got to do to get it right. In the end, you will have something you can be proud of. Winds of Skilak has won two book awards and today sits on Amazon’s Best Seller List in two categories, and has received rave reviews. I attribute my success to Inspiration for Writers, Inc. I have learned my lesson well and when my next book is written, I will save myself a whole lot of money, time, heartache and grief—I will make a beeline straight to Inspiration for Writers, Inc.

Publishing

I had often heard that once your book is written and ready for publication, you’ve only fought half the battle. I didn’t want to believe that. Actually, I didn’t believe it. However, once again, I realized I was wrong. No surprise there! I now had the daunting task before me of trying to publish and market my book. So many questions ricocheted in my mind. How do I publish? Who do I publish with? Do I try to find a traditional publishing company or do I self-publish? That was an easy answer for me. Having already run the gauntlet of submitting queries and proposals only to get rejections, I decided to self-publish. Now, that’s my personal choice. I’m not advocating that everyone should self-publish. For me, it was right. And again, you have to be proactive—it’s your baby and nobody cares about it more than you. There are many publishers out there, so you have to do your homework. In all honesty, I started searching my publishing options long before typing “The End” on my book. Once I made my choice and paid for my publishing package, I still had a lot of work to do. Don’t think for one moment that if you go with a self-publishing company, your struggles are over. I returned my manuscript many times to the publisher because of their formatting errors. I had to work to make sure they got it right. But, the day I held my baby in my hands, all the labor pains and hard work of giving birth to my story was replaced with indescribable joy!

The first step in marketing is to find your target audience. Believing your book will appeal to everyone is a big mistake. You need to define who will likely purchase your book, and then figure out how to reach those specific people. Where do they hang out? What magazines do they read? For instance, if your book is about hunting or camping or outdoor activities, you might see if you can put your books in a sporting goods store, or perhaps write an article or put an advertisement in a hunting or outdoor sports magazine. I recommend using social media, like Facebook (my favorite), Twitter, and Pinterest, just to name a few. Start a website and/or blog and engage your members, keep them motivated. Look for online magazines and blogs that appeal to your target audience and see if they will hold a book giveaway or give you an interview. Advertise in newspapers. And don’t hesitate to ask for reviews. Reviews are an author’s best friend and they do make a difference. Just remember, you can’t sit back and expect your books to fly off the shelves all by themselves. It takes work on your part. And, last but not least, if you have a well-written book with a great story, word of mouth will be your best advertisement of all.

It has been a pleasure sharing my experience as a first-time author with you, and it is my hope that some of the information I have provided here can be of some help—and for you new authors or soon-to-be authors out there, I wish you the very best on your journey to making your writing dreams come true.

Bonnie Rose Ward

Award-Winning Author of Winds of Skilak: A Tale of True Grit, True Love and Survival in the Alaskan Wilderness. After fifteen years as a “wilderness wife” in Alaska, award-winning author Bonnie Rose Ward now resides with her husband on their farm in central West Virginia. They still maintain a self-sufficient lifestyle, raising goats, chickens, and other barnyard animals, with four dogs and a peacock named George rounding out the menagerie. Bonnie enjoys canning vegetables from the huge gardens sowed by her husband with heirloom open-pollinated seeds, and in her “spare” time, she continues to write her memoirs of the Alaskan wilderness.